Slums and peri-urban areas: the key to rethinking post-COVID-19 metropolises

In 1854, a cholera outbreak struck London’s Soho neighbourhood hard. At that time, not even a society as advanced as that of England was yet prepared to offer decent urban spaces for its residents, and the pollution generated by the excrement of the city's own inhabitants was a permanent threat to their health. This episode, which was superbly reported in 2006 by Steven Johnson in his book The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic and How it Changed Science, Cities and The Modern World, has become famous for the maps used by Dr John Snow to demonstrate that the disease had its origins in water rather than air, as had traditionally been argued.

The great value of Snow’s discovery, as Johnson points out, is the way that his methods revolutionised both medical science and urban management. On the one hand, it was the first time that a public institution, the Board of Governors of the Parish of St. James, intervened in a public health crisis based on a reasonable scientific theory. And, on the other hand, Snow also pushed the local authorities to promote a series of large-scale civil engineering works for the supply of potable water and waste management (such as the Bazalgette Sewers Network). Such measures provided a foundation which permitted London -and later many other cities-, to accommodate millions of people and maintain a healthy environment to standards previously unthinkable.

What can we learn in terms of the management of metropolises from this case when we consider the current situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic?

The most immediate answer would be: we need to reinforce the links, which are still weak, between science and policymakers so that decisions made in cases like these are supported by scientific evidence. This also implies that we need to mobilize our skills in collecting and processing data relevant to the analysis of the situation and the monitoring of its evolution, using the increasingly sophisticated geographical information systems available. And finally, we must strengthen and expand our health infrastructures and services, which have been overwhelmed on so many occasions during the last few months after years of austerity policies.

However, if it really is to be a lesson on how to rethink our metropolitan spaces, as claimed by the Metropolis initiative, we will have to take a step further and tackle aspects that are perhaps not so obvious but that still affect the vast majority of metropolises when fighting a pandemic like the current one.

"Rethinking our metropolitan spaces means that this alliance must focus on resolving the problems of marginal zones and transition territories extending towards rural areas"

In this sense, if in the London of the mid-nineteenth century, with its two million inhabitants, it was necessary to make changes in order to make civilized life possible, changes such as the alliance of science, engineering and public policy action in order to provide it with the necessary infrastructures, what is the answer now? Rethinking our metropolitan spaces, some with populations ten times those of mid-nineteenth century London, if we want them to be liveable, means that this alliance must focus on resolving the problems of marginal zones and transition territories extending towards rural areas, which are the two main means to growth for the metropolis of the 21st century.

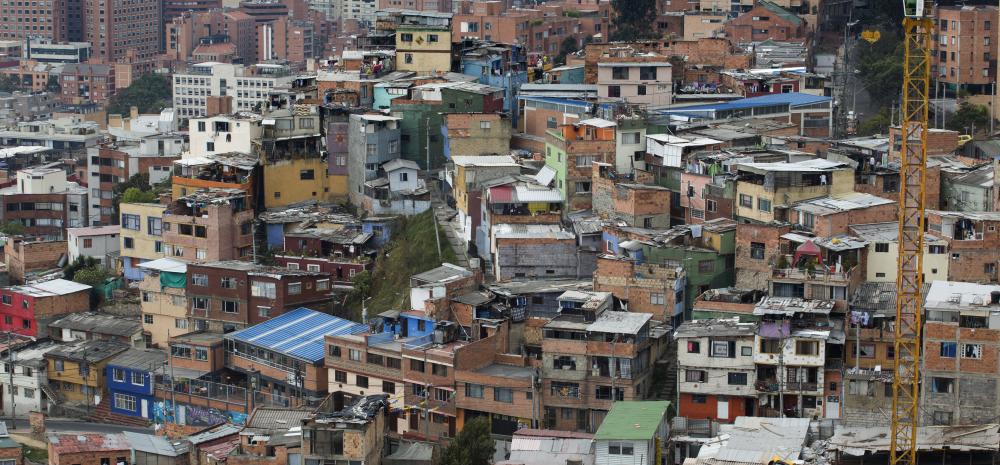

The situation in the slums, those places where there are still no infrastructure or services that would provide decent conditions for large numbers of people who live together, is critical. The poor housing conditions and the high levels of density act as very effective disseminators of the illness, much like water was in the epidemic in Soho. Dependence on the informal economy has also meant that widespread confinement has left them in an even more vulnerable situation. It is, therefore, necessary to act alongside communities to fundamentally transform these spaces and achieve a more organic integration into the urban fabric.

In terms of peri-urban spaces, the expansion of metropolises imposes the exploitation of natural resources which, for example, favours the proliferation of zoonosis, that is to say, of animal-transmitted diseases to humans. At the same time, the accelerated loss of food production capacity in metropolitan territories, in favour of territories increasingly distant from the centers of consumption, is an enormous weakness in the event of a crisis that obliges them to seriously achieve greater food sovereignty. The rise of metropolises should not overlook the important interdependencies between urban and rural spaces worldwide, as discussed recently in a webinar organised by Metropolis.

"By improving planning and management of slums and peri-urban spaces we would, therefore, be able to stop the next pandemic in time"

In short, while the issue of concentrating millions of people on a small fraction of territory has not been entirely resolved everywhere, the more difficult problem is the management of their interdependencies with the environment. By improving planning and management of slums and peri-urban spaces we would, therefore, be able to stop the next pandemic in time (or, better still, prevent the outbreak from happening). For these reasons, it is necessary to provide the most disadvantaged with opportunities for a decent life, to articulate the urban-rural relationships which are essential for territorial balance and the preservation of the environment and, ultimately, to guarantee that people in metropolitan regions can find a prosperous and hopeful future.

Oriol Estela Barnet: Economist and geographer. Local development and strategic planning professional since 1995, first in public administration consultancy (1995-2005) and subsequently in the Barcelona Provincial Council (2005-2016), with regular participation in various conferences, training activities and publications. He is the General Coordinator of the Metropolitan Estrategic Plan of Barcelona (PEMB) since 2016.