Going beyond city building: Culture-led urban regeneration

The accelerated process of urbanisation around the world in recent years has led to the emergence of urban spaces where residents’ quality of life is not guaranteed, and where urban regeneration projects have often been carried out, but have not always been successful. Within this context, on 14 December, together with the Municipality of Shiraz and the Mashhad regional learning centre, we organised a webinar on sustainable urban regeneration in which professionals from metropolises around the world shared successful cases of sustainable urban regeneration.

How do we want to shape and design global cities? This is the question that Octavi de la Varga, Secretary-General of Metropolis, posed to open the workshop, highlighting the role of citizens and cultural heritage in shaping urban spaces, giving each city and urban space a unique identity.

“Stakeholders, urban planners, academics and think tanks need to work together to rethink cities in order to guarantee residents’ quality of life, and make sure no one is left behind in urban development.”

Octavi de la Varga, Secretary-General of Metropolis

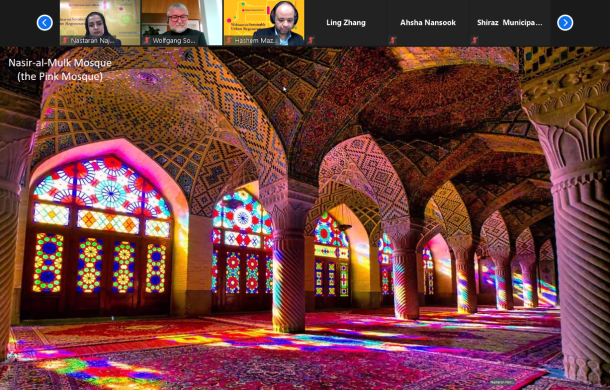

Currently, the Municipality of Shiraz is aware of the value of culture in sustainable urban regeneration and has undertaken a culture-led transformation of its historical district, which is home to 77,000 people and faces a number of difficulties such as urban poverty, crime, and a lack of social services.

Nastaran Najdaghi, Head of the Urban Regeneration Bureau in Shiraz, explained that culture-led urban regeneration is key for sustainable development, and went through the different steps to implement it: reorganisation, holding cultural events, land-use change, an urban renaissance in historical areas, the implementation of cultural projects and training for residents.

As an example, the abovementioned area was made up of 11 neighbourhoods. All the boundaries and functional systems were redefined, taking into account tourism development and residential needs. Besides attracting tourism to the area, the introduction of cultural events created a lively atmosphere in the neighbourhoods over the weekends, giving children the opportunity to play safely in urban spaces and allowing residents to make and sell their crafts.

Nastaran Najdaghi, Head of the Urban Regeneration Bureau, Shiraz

Similarly, in the city of Dresden, a number of projects have been implemented to upgrade the city centre by developing a green belt. In addition, mixed land use was encouraged with the following mission statement: a compact city and an ecological network. The landscape plan sought to improve the interconnection between green areas in order to better adapt to climate change, but it also served as an opportunity to improve water management, sustainable mobility and improve links between the city centre and the surrounding areas. Citizens were involved from the beginning of the planning process, which lead to high levels of acceptance.

Finally, Nanjing’s experience of urban regeneration has shown the contrast between two different approaches, a top-down model in the Old Mendong area and a bottom-up model in the Small West Lake area. Ling Zhang, Deputy Director of the Development and Reform Commission of Qinhuai District, Nanjing, shared several urban regeneration actions that took place in these areas with the other urban practitioners, revealing that even though the decisions were made much faster in the top-down model, the bottom-up experience led to greater acceptance among residents, allowing them to express their needs and enabling a greater problem-solving capacity during the urban regeneration process. Through this approach, citizen involvement makes urban development more efficient and sustainable

Ling Zhang, Deputy Director of the Development and Reform Commission, Nanjing